Where are the charge points?

Charging anxiety takes over from range anxiety for potential EV buyers

Motorists are now more worried about the lack of electric charging infrastructure than they are about how far the vehicles can travel per charge.

These are the views of Mike Hawes, head of the trade association representing the British car industry.

Positives and negatives

The UK public are moving away from ‘range anxiety’ (the fear of running out of battery while en route somewhere). Instead, ‘charging anxiety’ is replacing the fears. This is because the number of public chargers is not increasing at the same pace as sales of plug-in vehicles. Furthermore, the vast array of providers means multiple phone apps and paying methods. On top of this, access to working chargers is being hampered by faults and parked cars in charging spaces.

Mike Hawes, chief executive of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), was speaking at the SMMT Test Day. This is an annual driving event for members of the UK press.

“Back in 2011, when we first started having some electric vehicles here at Test Day, the average range [of them] was only 74 miles,” states Hawes. He adds that there “were about six cars” on the market.

Now there are “about 140 and the average range is increasing dramatically; potentially an average of about 260 miles”.

“So you can see how the technology is really developing. And that’s fundamental to the take up of these new vehicles. But what we’re constantly hearing from owners, users and so forth, is that the range anxiety is now being replaced by charging anxiety.”

Charging up

The number of public charging points in the UK has increased 33% over the last 12 months. There are 30,412 chargers available today at 19,150 locations, according to figures from Zap-Map.

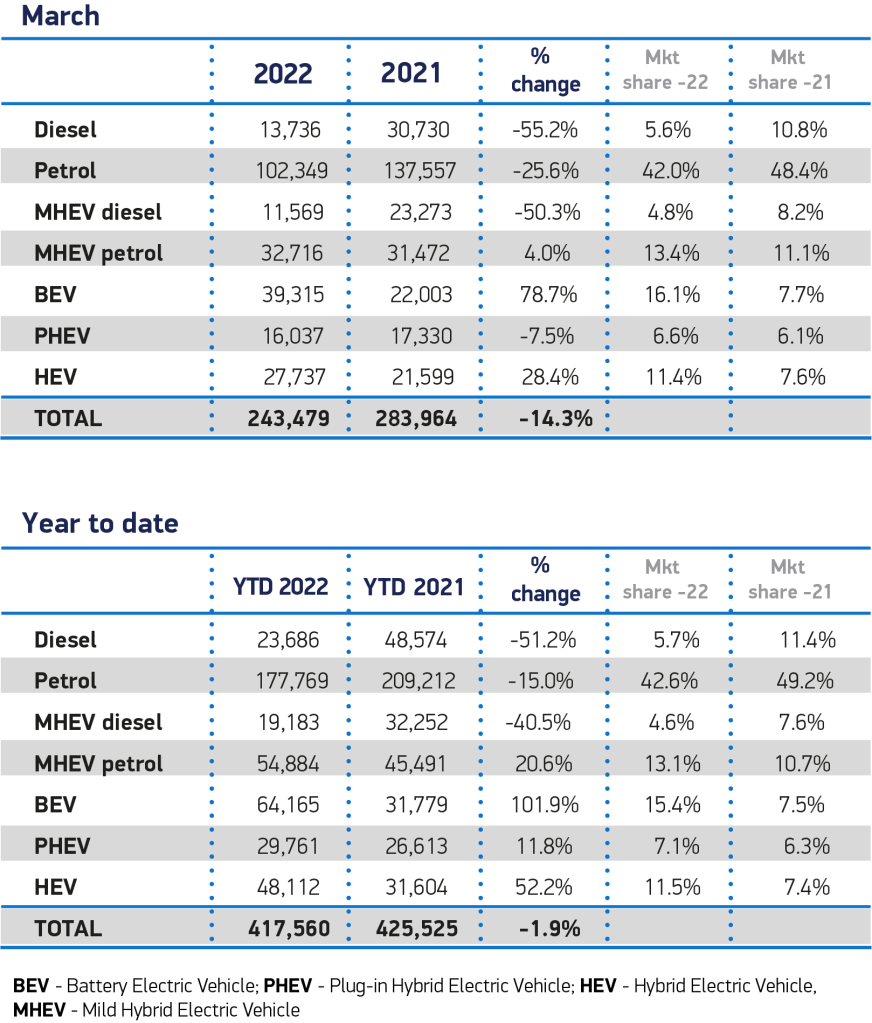

However, there has been a huge increase in the sales of electric vehicles. Figures from the SMMT for March showed a 78.7% year-on-year rise in the number of electric models sold. The 39,315 electric car registrations is nearly three times higher than the number of diesel cars sold last month. Battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) now make up 16.1% of all registrations.

Plugging in

Last year, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) said a charge point provision needs to increase dramatically in order to meet the growing demands. Public chargers will need to increase to between 280,000 and 480,000 by 2030. This is when the ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars comes into effect.

However, it seems that the demand for infrastructure is already struggling to meet expectations.

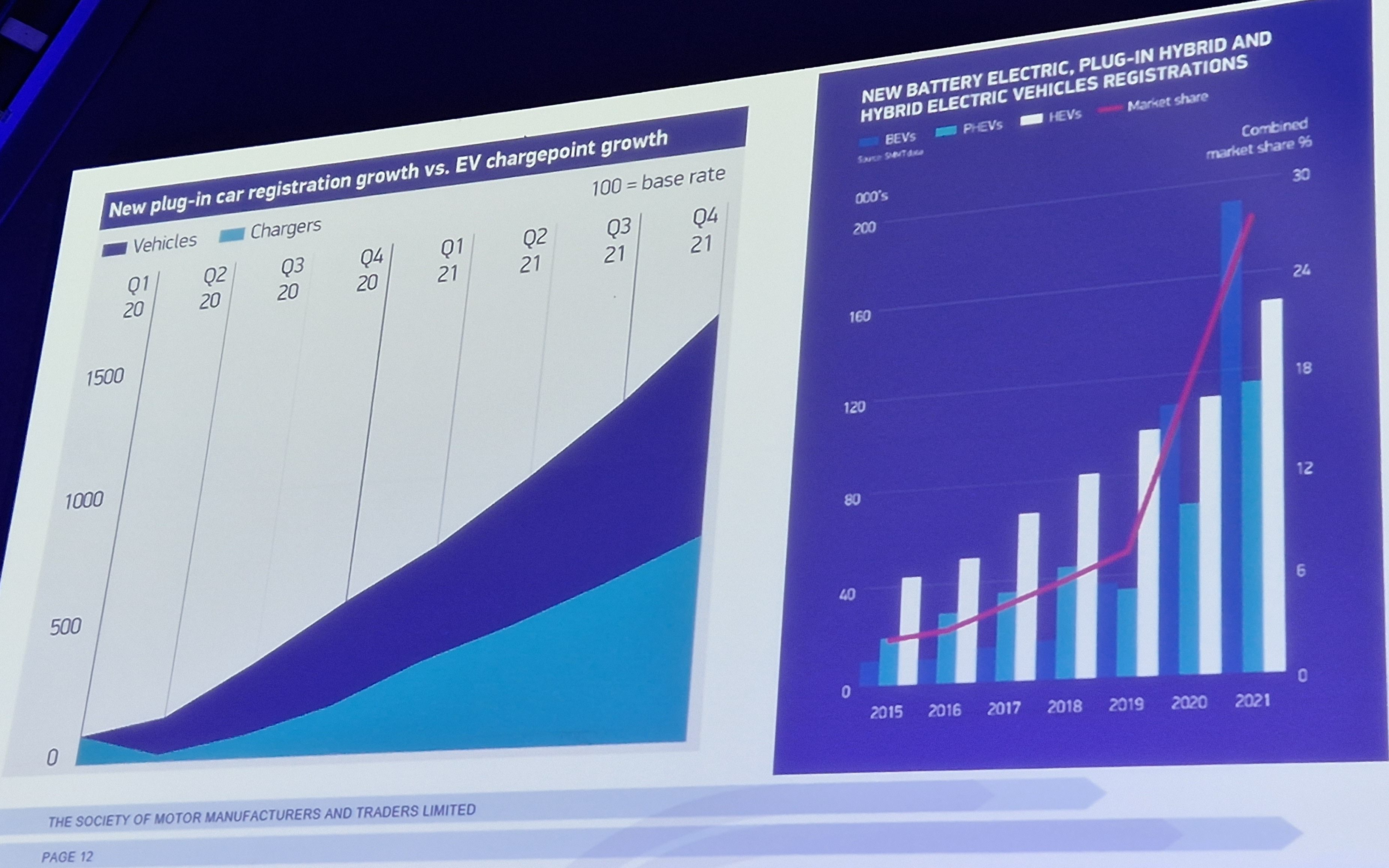

Hawes showed a graph comparing electric vehicle sales volumes over time with the rollout of public chargers in the UK. It shows not only that electric car sales are outstripping charging infrastructure installations, but that the gap is widening.

“The increase in investment in infrastructure is increasing, but it’s not catching up,” says Hawes. “It doesn’t match the increased sales of new cars.”

“We need it to catch up to overcome what most people’s concerns are,” adds Hawes. “I said before, is not range anxiety, it’s charging anxiety.”

Pocketing the difference

The increase in EV sales comes despite “poor incentives” from the government. This is another issue for the industry and improving sales in what is a decline in new car sales. Economically, the affects are huge for an industry that has invested heavily in the tech, but is struggling to recover from the negative effects of the pandemic.

In 2011, a year after Nissan introduced the pioneering Leaf hatchback, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition introduced the Plug-in Car Grant. This was a subsidy of 25% off the price of a pure-electric, plug-in hybrid or hydrogen fuel cell car, up to a maximum of £5,000.

Since then, subsidies have been cut five times. Car buyers today receive £1,500 off the cost of a new pure-electric car with a value up to £32,000.